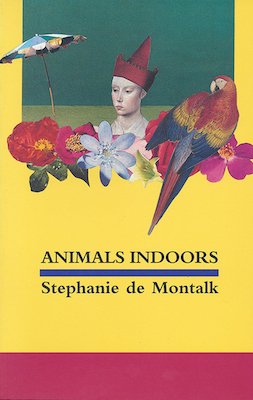

Cover Design

Brendan O'Brien

Victoria University Press, 2000

These poems, set at home and abroad, balance the mundane with the mythical. Children grow up. A Russian sailor abandons his ship in Timaru. A prospective handyman lays rite-of-passage concrete steps on a hillside. A bystander in court bemoans the ‘lunacy’ of jury trials.

Edward Barnes gets himself into a ‘hell-hole’. A surgeon’s body leans against his coat. Carpets are purchased in Afghanistan. The trunk of an oak tree runs away from its roots. An amah sweeps an ancestral grave in Hong Kong.

AFTER JUVENAL

(‘Satire 1’)

Must I always remain in the crowd at the back of the room

as the barrel is rolled, and the names are called, and the white

squares of paper are flattened, with finality, on the bench,

never to be called to the platform, paraded before counsel, or permitted

The dramatic moment of decision – the Bible, or individual

affirmation –

or closure in the windowless room with the water closets, circular

table, and tea and coffee making facilities,

never

to take dinner in a nearby hotel, and a bed near midnight

and the shrill sound of the city,

never to close the gap

or be close to the gap?

Is there no recompense for the John Grisham novel, and repeated

screenings of Twelve Angry Men, and the dissertation

on statutory interpretation, read at the kitchen table, fingers iced

to the page,

or the definition

of reasonable doubt which came to me on a hot summer’s day as I

stood by a river of unknown depth, and wondered whether I should

dive, or simply slip in from the side?

I know my chances are not good:

I wrote ‘Nincompoop, Financial’ on a form for the electoral roll

and was thereafter marked ‘Occupation Not Stated’, although

a friend who is a Secretary, and put herself down

as a ‘Trapeze Artist’, was not overlooked.

Need I speak

of the frustration that burns in my heart

as the last seat is filled without me, as I am forced to adopt the aura

of bystander, the colour of dullish hue, the dance song without

a refrain,

to leave like a lover who has been warned in the night

by a watchman?

Am I never

to draw reasonable inference, argue the fact, or enter the ghostly

and hostile territory of the guilty mind?

never to know the challenge of thinking in a small space, listening

to the gnawing of the favourite bone in a small space, the simplicity

of raw beginnings, the failure of elaborate language, the feeling

of being squashed like a grape in a punnet or plastic bag

for the day, in a day a little out of the ordinary?

Surely

a Nincompoop, self-declared, who has stood at the river of uncertain

depth and applied the principle of reasonable doubt, is a safer

proposition than someone who has not dived without doubting,

or doubted without diving?

Has the Retired Builder, who folded his arms, and sat back

in a comfortable, calm and cloudy day kind of way, ever wavered?

or the Retired Nurse who will take off her jacket at the circular

table?

or the Primary School Teacher who left her Mitsubishi in a church

car park?

Will they suffice?

How about the Student Who is Majoring in Classics, and living

at home with hopes of becoming a librarian, and was fixated

with the bow tie of the defence counsel?

and the Housewife who was worried her family

would have to get their own meal if the case lingered

on into evening, even though she had left mince in the fridge?

and the Trainer from Trentham, who was up before dawn

and tense away from the subject of horses?

What about the Theatre Nurse who has a ticket to Saudi Arabia?

Will these people suffice?

The Superannuitant was called. She said ‘God!’ (with all reverence,

so she wouldn’t be struck down), and declined a Bible,

and the Programmer went forward, clouds banking, rain

trailing, to place evidence, like troupes of tame sparrows,

on the whiteboard, pursue the flicker of breadcrumbs, the results

of a coupling, and the salted peanut which might fall

from a casually discharged packet on a lean winter’s day,

and the Enthusiastic Woman with a short skirt, and new briefcase,

who did not believe an undercover cop could be a reliable witness.

Will the verdict be a farce?

Is it not possible

that one or more of the remaining three – the Lighting Technician

in black , the Porter who was born in Macedonia, and the Gentleman

of Methodical Appearance, who might once have been taken

for a diplomat –

have squandered a family fortune, cultivated cannabis, or placed

semi-defective parts in a second-hand car or washing machine,

before selling them?

Is it not lunacy

that a group so lavishly inconsistent, should be expected to reach

a unanimous decision in the absence of voice-overs, reruns,

and preconceived points of the compass?

Imagine the confusion

as an honest belief becomes a colour of right,

as those who filter in colour turn their minds to purple and yellow

and blue, address the subject of goats’ hair and linen,

the development of synthetic dye, a chance discovery

in a laboratory, and the wild success of mauve,

while those who have stumbled on right debate the fugitive nature

of freedom, and foresight,

and the rest are adamant they are not mind-readers.

And so it wears on –

the scrambling of names, the lottery, the ships drifting

in Cypriot harbours.

The clerk enters the court, the prisoner is placed in the dock,

and the judge hitches up her dress before she sits down.

Not

since the great days of the Flood

has there been any sense.

Winner, Jessie Mackay Award for Best First Book of Poetry at the 2001 Montana New Zealand Book Awards.

‘Stephanie de Montalk writes with unusual grace. [...] Although she might be telling a straightforward story or describing familiar objects, there is

also often a sense of mystery. A fleeting detail, clear in itself, will suggest something beyond. [...] Cool and steady these poems set off many small

resonances.

Guy Allen, ‘Supple Artifice’, Weekend Herald, 25—26 November 2000.

De Montalk’s talent lies in gentle satire, graceful endings and musicality [...] One of the most engaging things about [her] work is her obvious

interest in the dynamic between two people. [...] I was left with the impression that silences are what interest de Montalk most. What is unsaid [...] in

the pause between stanzas as we digest what has gone before and in the dying away of the last line of a poem.’

Paola Bilbrough, ‘The Rhythm Method’, New Zealand Books, December 2000.

‘Stephanie de Montalk [...] makes an impressive debut [...] Her poems are relaxed, articulate, knowledgeable, meticulously observant, focusing on

others more than on herself. Many could be called portraits in context, particularly of people at work or going about their everyday business. They

often extend to several pages and in their fullness achieve an empathy that brief quotation cannot adequately convey.’

Gerry Webb, ‘Wild Things’, New Zealand Listener, 5 August 2000.

‘ ... a mature talent and impressive poise. De Montalk’s air of studied nonchalance effects liberation from everyday constraints even while

acknowledging their existence. [...] As a collection which affirms that life needs art, Animals Indoors makes rewarding reading.’

Janet Wilson, ‘A Flair for the Theatrical’, The Evening Post, 27 October 2000.

‘ ... poetry that more than most has [...] an objectivity that allows her to present a clear-eyed, uncompromising view of the world it relates to. A sure and certain ear keeps the work totally free of tired language and cliché so that every line is fresh and rings true. [...] there is an obliqueness about the writing that implies a metalanguage behind her work.’t Alistair Paterson, Poetry New Zealand 21, 2000.

‘An impressive debut collection, testament to the author’s wide range of interests, and sympathetic observations of human behaviour.’

Booknotes 131, Spring 2000.