Stephanie de Montalk

Stephanie de Montalk (1945) is the acclaimed New Zealand author of four books of poetry, a novel, a study and memoir of pain, and a biography-memoir of New Zealand poet and eccentric, Count Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk.

Stephanie de Montalk (1945) is the acclaimed New Zealand author of four books of poetry, a novel, a study and memoir of pain, and a biography-memoir of New Zealand poet and eccentric, Count Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk.

Stephanie was raised in the Far North of New Zealand, and later in Wellington where she and her husband still live. A former nurse, documentary filmmaker and member of the NZ Film and Literature Board of Review, she came to writing late, in her fifties, as family and work commitments lessened. Since that time, her writing has appeared in literary journals in NZ and abroad, been read on Radio NZ, and frequently achieved 'best book' status. She has also been the recipient of multiple awards, notably: the 1997 Victoria University of Wellington Prize for Original Composition ('Notes Along the Cool Edge of a Page', poetry);

the 1997 Novice Writers' Award in the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Awards ('The Waiting', short story); the 2001 Jessie Mackay Award for the Best First Book of Poetry at the Montana New Zealand Book Awards (Animals Indoors); a 2015 Nigel Cox Award at the Auckland Writers' Festival (How Does It Hurt?, a study and memoir of chronic pain). She has an MA (Dist.) and a PhD in Creative Writing (VUW). In 2005, she was the Victoria University Writer in Residence. From 2003, when an accident during a research trip to Warsaw caused the onset of intractable pain, her work has explored states of isolation and constraint: concerns that informed her PhD.

"De Montalk has a fine sense of narrative restraint and irony. [...] The language is at once clear and Latinate, cultured, measured, controlled and understated. It gathers in a sheaf of references not only to high art and history, but also to the sciences. I almost want to call it the poetry of good manners - particularly for the way de Montalk transforms, deflects and even sublimates the pain of a serious accident [...] Cover Stories indeed. The germinating subject of this series is, apparently, a broken pelvis: yet here, stoicism is an art form. [...] A single transferred epithet tells us something of the mental fortitude it takes to use proverbs and elegant images to translate the experience: 'That summer she lay altered/for months/ one eye on the floor .../a merciless light at the window".

'de Montalk's tense, restrained minimalism is capable of packing a punch. [...] The poems about the author's pelvic injury and subsequent surgery are particularly vivid. [In 'Hawkeye V4'] it is only de Montalk's consistently spare style that makes this poem's haunting evocation of the patient's powerlessness in the face of medical technology moving without sentimentality: at once profoundly unsettling [...] and oddly comic. This is a remarkable achievement in the control of tone.'.

'It is always exciting to receive a book of poems by Stephanie de Montalk. [...] Her poems are compact but always dense with meaning. Occasionally there are sharp scratches of sheer joy, at other times her poems are quite hypnotic. [...] Cover Stories is full of genuinely beautiful poems [...] far more than simple cover stories.'

' ... the assured and confident voice of a poet in full command of what she is doing - a poet whose easy, conversational mode is immediately attractive, immediately evocative of her life - the ordinary and sometimes extraordinary events of everyday - and the lives of others.'

'She knows about many things. [...] She writes with ease [...] She selects details which are fitting and which suggest more than they actually say. [...] de Montalk can also write with dazzling simplicity. [...] To write with grace about sickness and surgery is a difficult thing to do. To write about Lourdes without being sentimental or cynical is not easy either. [...] These thoughtful poems are well worth reading and reading again.'

' ... language that is so carefully picked that it is at once delicate and lush. [...] a scent of European exoticism [...] a strong, unique voice [...] 'Otherwise', Real and Imagined', 'Hawkeye V4' and particularly 'Talking Pictures' have a particularly interesting point of view. Simultaneously submissive and astute, the characters in these poems [display] cool vividity: 'he scoops the air/as if filling/a copper bowl/with hot water' the narrator of 'Talking Pictures' says, describing the actions of a surgeon across the other side of the world performing an operation via the telephone.'

‘De Montalk has produced a book full of candour and feeling. It has a real depth to it. [...] The reader is left reflecting on acts of kindness, the quiet of the night, fires being lit, “the sky sailing, rolling gently”. I loved the beautiful stark imagery in ‘Violinist at the Edge of an Icefield’ and the possible tribute to Leonard Cohen in ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’. [...] an amazing follow-up to Animals Indoors. [...] This is really tender, lush stuff. I think I have been seduced.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk returns with more of the graceful and gracious writing that distinguished her first collection. With what has been described as a great sense of the theatrical, de Montalk eloquently writes about the “alchemy of everyday life”’.

‘ ... complex, extended pieces, playing with the sensuality of language and sound, yet withholding meaning, offering instead a series of beautifully honed images, which circle round the trivial and almost humorous. [...] In the opening poem de Montalk writes of “the art of penmanship – /the whole art, that is/ of legibility” as “an act of trust”, and it is in this spirit that these poems should be encountered. They do not disappoint.’

Dr Wang’s evidence might be scientific, but de Montalk’s observations of people and the way they speak is also reliable and very astute. [...] Not for quick or careless reading, these are poems to work at, but treated thoughtfully they yield good things. Their best gift is a sharpened awareness that there is more than one viewpoint for everyday life. If or when I enter the imperial villa I shall take my copy of this book. It may help preserve some originality, humour and kindness.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk’s second volume delicately circles “the art of penmanship”. It is a most worthy successor to her award-winning Animals Indoors. Fresh, precise and elegant The Scientific Evidence of Dr Wang presents itself in three parts – the first a series of charming profiles of a retired barrister, an exercise master, a dissident, an artisan, a solderer and more. Part Two is more personal with intimate snapshots [...] And Part Three opens the door on the world outside. A sturdy subtext underlies each piece, whether it be a fanciful opinion about the habits of Mrs Pobjoy, the last mistress of Beau Nash, who after he dies “recovered her sense of theatre and original freshness, learnt to be patient” – or a story of ancient Mesopotamian hero Gilgamesh who each morning “whistles as he greets the sun – clad as if for a courtly encounter”’.

‘ ... poems that echo the tone of the historical narratives of the Greek poet Cavafy. [...] Many of the poems show a particular strength in providing details which make real what experience is like – the “thickness” of experience – rather than giving a sense that the images are carefully chosen correlatives for something else. [...] De Montalk likes to take on big topics: colonialism, displacement of peoples, varieties of loss, death and grieving. Here she operates with a light touch, with an awareness of the cyclical nature of these events. [...] In the concluding poems [...] she returns to simplicity and intimacies, the images pared away to bareness. This gift for simplicity remains the strongest impression from this collection.’

‘Precision of language; intimately tactile attention to detail; sensual flourishes; allusiveness – these are the things that make de Montalk’s poetry such a pleasure. Her collection’s first section explores the hopeful projections and intractable realities of the colonialist; the extraordinary second section is one long poem, Feathers and Wax, in which she imagines herself rapt away from everyday life for a magical mystery tour on an aluminium-clad blimp with a mysterious pilot and ‘decidedly unorthodox crew.’

‘... even when taking a holiday from plain sense, de Montalk continues to grip us, as everywhere in this volume, with the probing intelligence and nervous energy of her language.’

‘ ... a writer unafraid to use her intellect to approach themes that enthrall her. [...] The long, central poem, “Feathers and Wax” [...] transcends the nuts and bolts of story and reaches towards the sublime.’

‘She keeps her form going and she does what she does best. She gives the reader glorious, contagious, memorable compact poems. [...] Dark intoxicating poems duck and weave between multilayered thoughts, confounding expectations – but always retaining a cheeky, charming commonsense. [...] De Montalk is enlightened and it comes through in her poems.’

‘ ... the language is often used sparely, to exquisite effect: “Creeks swam/or evaporated; The children licked jam spoons/so that nothing was lost.” The best of these are poems in their own right: “See how happy you are/Stirred/With a long spoon.” Remarkable characters emerge throughout the book; all are elusive. [...] I was left with an appetite for more.’

‘I’ve already been caught intoning lines from ‘Consultation’ not quietly enough. [...] Now I truly must get around to reading The Fountain of Tears.’

‘[de Montalk] employs the orator’s rather than the singer’s art [...] In some poems the voice is edged with an impish sparkle or even a hint of defiance. In the colonial poems the same declarative quality is made to sound faintly archaic, evoking a period persona, while admitting a cool hindsight; no small feat of what Bakhtin called “double—voiced” utterance, the duet between writer and character conducted with a remarkable economy of means. [...] The centerpiece of the collection is ‘Feathers and Wax’, which is not just another updated Icarus, but a tour de force the fabulist’s art. [...] The poem is enchanting, an exuberant fantasy [...] a world experienced from the “aerostat” as pure perception, almost without reference. There is exaltation and impish humour, and esoteric learning deployed with a light touch – the ingredients of many of the poems, but in different proportions.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk writes with unusual grace. [...] Although she might be telling a straightforward story or describing familiar objects, there is also often a sense of mystery. A fleeting detail, clear in itself, will suggest something beyond. [...] Cool and steady these poems set off many small resonances.’

‘De Montalk’s talent lies in gentle satire, graceful endings and musicality [...] One of the most engaging things about [her] work is her obvious interest in the dynamic between two people. [...] I was left with the impression that silences are what interest de Montalk most. What is unsaid [...] in the pause between stanzas as we digest what has gone before and in the dying away of the last line of a poem.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk [...] makes an impressive debut [...] Her poems are relaxed, articulate, knowledgeable, meticulously observant, focusing on others more than on herself. Many could be called portraits in context, particularly of people at work or going about their everyday business. They often extend to several pages and in their fullness achieve an empathy that brief quotation cannot adequately convey.’

‘ ... a mature talent and impressive poise. De Montalk’s air of studied nonchalance effects liberation from everyday constraints even while acknowledging their existence. [...] As a collection which affirms that life needs art, Animals Indoors makes rewarding reading.’

‘ ... poetry that more than most has [...] an objectivity that allows her to present a clear-eyed, uncompromising view of the world it relates to. A sure and certain ear keeps the work totally free of tired language and cliché so that every line is fresh and rings true. [...] there is an obliqueness about the writing that implies a metalanguage behind her work.’

‘An impressive debut collection, testament to the author’s wide range of interests, and sympathetic observations of human behaviour.’

‘Every once in a rare while, a subject and an author admirably suited to each other connect and the result is a book of outstanding interest and merit. Unquiet World is one such volume. [...] [L]ike most poets [de Montalk] writes prose very well. This quality is yet another that lifts this book from the domain of biography into that of literature. What she has to say about de Montalk senior is clever, vivid and clear. She presents the crumbling Provencal villa in which he lived his last years as a metaphor for his entire life. And her asides are devastatingly apt. [...] The book does what every good biography should do. [...] It has to be a favourite for the newly introduced category of biography in next year’s Montana Awards.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk succeeds in bringing her implausible relative to plausible life. His various exploits on a world stage are set in a meticulously researched analysis of the context of its times, and in openly acknowledging a complex and shifting personal relationship with her quarry, she charts the subjectivity that must go into the making of any biography.’

‘ ... a magnificent humane book [...] which also happens to be one of the best books of 2002 (even though it came out at the end of 2001).’

‘ ... a judicious, stylish and entertaining book. De Montalk (the author: she calls her subject, as he would have wished, Potocki) wisely decided against the kind of biography, with every day accounted for and every fact footnoted, that is a reward, or punishment, for tangible achievement. [...] She puts herself in the picture, pursuing her cousin: a quest for Potocki. He was in many respects a classic eccentric. De Montalk has read the literature on eccentricity, but she has not been content to dismiss him with a label. She has sought the springs of the man behind it. She has been thorough. From time to time I quibbled and asked questions – ‘Is she too indulgent of his outrageous bigotry? What does she really think of his poetry?' – then found her grappling with the same questions.’

‘[de Montalk’s] narrative of NZ literature’s most spectacular expatriate is one of the most consummate and compelling stories I’ve read ... well, this millennium. [...] [She] lucidly outlines the passions that endured through the posturings: fidelity to free speech, Polish integrity, the immanence and permanence of beauty. [...] She’s quite a presence in the narrative.’

‘The book is a witness to deliberations and search for a method of unraveling a difficult personality. It seems the author, writing about Potocki, sketches her own portrait, which to me appears more alluring than her subject. [...] What then are Potocki’s achievements? The book indicates that they are the reprints, translations and verses. But the greatest achievement [...] is Stephanie de Montalk, who undertook the task of finding some sense to his life. The result is a quality product.’

‘[Her] explanation of the Count’s obscenity trial is masterful in the thoroughness and precision of her analysis. It should be used as a model of how extra-legal factors affect outcomes in every law school’s “Law in Society” course. [...] The book ends with the funeral of an unnamed stranger in France, coincidentally taking place near Geoffrey’s grave. The stranger's family will never know they close one of New Zealand’s best memoirs.’

‘This fascinating book [...] is not a standard biography [...] Rather, the arrangement of the material largely reflects de Montalk’s search to understand a cousin whom she liked despite major differences in political and social values. (And I also imagine, despite Potocki’s considerable charm, his ability to be exasperatingly himself.)’

‘Potocki’s extraordinary career is examined – with sympathy but definitely not without criticism.’

‘What makes the journey in pursuit of [Potocki] is the calm, honest guide that cousin Stephanie proves to be. [...] Stephanie’s book, based on personal interviews, observation and careful study of a mountain of mouldy papers, is a fascinating peeling back of Potocki’s personality.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk’s engaging memoir/biography [...] gives a provocative perspective on one of New Zealand’s more enduring eccentrics. [...] [She] has done a service by restoring [Potocki] to a richer view, and providing a necessary lens on eccentrics in general.'

‘[De Montalk] does not attempt to write a traditional scholarly “objective” biography, but rather she tells both [Potocki's] story and, at the same time, the story of her and her family’s relationship with him in his later years, and of her own attempts to understand him and write this book. The result is a sympathetic portrait of a man who might have been treated as a figure of fun, and at the same time an honest account of her attempt to come to terms with his extreme self-centeredness and eccentricity and to see their probable origins in his painful upbringing by an authoritarian stepmother and several aunts. The book is a sensitive exercise of sympathetic imagination.’

‘Stephanie de Montalk does better justice to her second cousin than any mere review. This critical biography of a difficult, colourful aristocrat makes us yearn for the eccentric.’

‘A jewelled box of mirrors [...] This may be the most exotic story yet written in this country. [...] Stephanie de Montalk is at once our Scheherazade and Pushkin, Ovid and his Nightingale Philomela, singing a rare and complex melody [...] Imagination is not just the engine that drives the writing: in this novel it is almost a force of of the nature. [...] New Zealand writing is the richer and lovelier for it.’

‘A high quality work of intellectual fiction [...] a powerful and compelling re-creation of two parallel situations and personages [...] a valuable work [...] rich in biographical, psychological, and mythological contexts, precise in many details concerning both Pushkin’s childhood and youth and the complex phenomena of Eastern European history and culture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and profound in its exploration of the themes of creativity, of responses to surrounding reality, and of the (re)creation of one’s personality in letters, dreams, life and art.’

‘... dense with imagery and suggestion [...] When I had finished reading it, I turned back and read it again. It’s a book that rewards close attention, and – like Maria [who keeps the khan at a distance] one that refuses to give up its treasures easily. [...] It offers much to admire, to listen to with the inner ear, to savour, to ponder and to puzzle about. My recommendation is to [read this book] at least twice. I’m not joking – it really does reward that effort.’

‘The language is consistently rich, often purely beautiful. Montalk is a poet: “The moon flings dust in Maria’s face: the dust of bakeries, vegetable sellers and barbers; the white dust of the poplars behind the Great Mosque.”’

‘Fantastically ambitious [...] a sort of imaginative recreation of an imaginative recreation [...] I think it’s wonderful [...] a remarkable book [...] She has Pushkin imagine at a certain point, “as long as the chronicled air is breathable historical approximation is sufficient”. And this chronicled air is definitely breathable.’

‘Invariably and stylishly lifted by sweeping movements of plot and language. [...] The plotting of The Fountain of Tears is one of its great pleasures.’

‘... a singular achievement [...] De Montalk removes Pushkin from the literary canon for a day so that we may get to know him as a living man, before his works have gained their place on the world’s bookshelves. [...] One feels a greater affinity with Pushkin after reading this book and seeing him wrestle with captivity and memory in the early hours of an Odessa morning. [...] Ultimately the two stories, and their two vanished characters, intersect through a physical medium, the fountain of tears title. [...] the worlds of Maria and Pushkin are successfully evoked [as are the story’s] meditative explorations of the ideas of captivity, memory and the fluidity of time. [...] a further development from an original and innovative New Zealand writer.’

‘I am surprised that Stephanie de Montalk is the first (as far as I know) to put this rich, romantic material to good use, in the form of a novel generously interspersed with verse. De Montalk’s experience as a poet and biographer makes her the ideal author for such a pursuit.’

'This is a wonderfully powerful, important, and beautiful piece of work which makes a major contribution to the understanding of the subject of pain. The success of the project lies in the fact that the author illuminates the ugly problem of pain, from so many angles, using so many light sources, with such beauty.'

'How Does It Hurt? reminds us that some of the most notable and innovative intellectual and artistic figures were people with disabilities – and that the history of creativity and the history of living with suffering are inextricably intertwined. Stephanie de Montalk's own contribution is a riveting and compelling read.'

‘[H]ighly absorbing [...] She gives Daudet a voice, imagines his character based on his writing, imagines how he might sit, speak and act, while [...] moving through meditations on chronic pain and suffering. A truly masterful piece of writing.’

'This book broke me and healed me [...] and I think I owe it a debt of gratitude for kicking me into the world of memoir and non-fiction appreciation. It's VUP, for one thing, which is one of those easy marks of calibre. But the deeply personal story of pain, ever present-pain, struck a chord with me. [...] Pain, yes, but more than that, the experience of chronic illness and pain in a world ill-equipped to deal with that mode of being. It's eloquent, it's heart-breaking, it's everything a memoir should be.'

‘[A] work already recognized by health professionals as ground-breaking and riveting and beautiful […] The book is political, fierce, open, buzzing with ideas about how the body treats the mind and vice versa. It’s an unflinching account, terrifying and bleak in its tracing of nerve pain’s unpredictable torture methods […] Books like this one remind us that we should never get used to anything.’

‘A magnificent memoir by a brave, brilliantly articulate and insightful woman […] A deeply personal, moving, beautifully written account of a life lived with a constant companion: chronic pain […] Doctors need to become more interested in the people they are seeing than the things they are doing to them. Patient stories are a tool in achieving that, and de Montalk’s memoir serves that purpose well. However it is much more than that. While documenting her relationship with chronic pain, de Montalk articulates a love of literature with three case studies of famous writers who suffered similarly to her […] Those of us who work in the health system are often inspired by patients who respond to great adversity with resilience and fortitude, and with compassion and generosity towards others, but few have de Montalk’s ability to articulate that in such a meaningful and accessible way […] It is a book that will help all those suffering from chronic pain, and those who care for them and those who love them.’

‘This is a superb book which should be compulsory reading for all health practitioners who are ‘in pain’: Stephanie de Montalk challenges us to comprehend the meaning of pain.’

‘Every medical person in the world should read this.’

‘She tackles the subject with precision, compassion, eloquence and infectious curiosity […] Stephanie’s deft hand weaves stories that spans centuries of pain experiences […] Not only is the academic writing deeply satisfying, the poetry is profound, the personal narrative far beyond moving, and the book as a whole is a totally unique resource for sufferers, carers, and anyone in the medical profession.’

‘[T]he book might even do for the subject of chronic pain what […] The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion has done for grief.’

‘[T]he most wonderfully readable and moving account of chronic pain […] like Joan Didion’s book The Year of Magical Thinking […] an incredibly coherent work […] like a documentary film where all the parts are brilliant and the whole is extraordinary.’

‘[E]xtraordinary […] It puts me in mind of Vera Brittain’s classic memoir of WWW1, Testament of Youth, for its lucidity in the face of the unbearable, and its role in bearing witness. De Montalk’s beautifully written, important book tells those of us who haven’t known the ordeal of chronic pain something of what it is like for the increasing number of people who live with it.’

‘A truly remarkable book about what language is, how far language can go, the relationship between language and the human body and mind […] A meditation- essay on chronic pain […] segues into lilting, plaintive poetry […]Most people have experienced at one remove or less the kind of things she is talking about […] a breathtaking book, a remarkable book. I think it’s probably my book of the year.’

‘She is a wonderful writer as well as a thinker […] I’d say she’s one of our country’s philosophers, in fact […] She’s looking for the language to describe [chronic pain] […] She goes very broad in trying to express it […] She expresses the thought that great pain, chronic pain, can push you into great creativity because your physical life is proscribed, but also because you become intensely sensitive to others […] The power of this book is not just about making us see chronic pain differently, but that we see how anyone that suffers something chronically lives. […] I felt that anyone with a mental disorder, a disability or even grief, something that is wrecking or driving their lives, she helps us see inside this, the chronicity of it that never ends […] It stunned me […] it’s a wonderful, wonderful book. I hope that it will feed into an argument in which we would all be more tolerant of the people around us.’

‘A moving account […] beautifully interweaves literary references […] [Acknowledges that] chronic pain is a deeply alone thing […] You’ve given those who live with chronic pain something special with this book. It’s a fantastic read.’

‘A riveting read […] compelling […] a clever blend of memoir, academic research, imaginative biography and poetry […] She does not shy away from writing candidly and eloquently about the solitariness of pain and her own experience.’

‘De Montalk has deftly grappled with the subject of chronic pain from a personal, academic and poetic point of view […] a beautifully written, fascinating and insightful work.’

‘[A]n extraordinary memoir […] explores the reality of pain, why it is so difficult to talk about and understand, and how the lack of conversation contributes to disbelief and isolation […] Calling the book a memoir fails to capture the power, rarity and complexity of both the content and the author.’

‘Chronic pain is shown here as an affliction with all the distress of a terminal affliction, but none of the latter’s “heroism’ […] It’s perhaps the loneliest of all physical miseries. Surgery, constant medication, travel, time as Victoria University’s Writer in Residence where she worked at a standing desk, debilitation and exhaustion, medical optimism, ingenuity and helplessness, the seductions of ending it all: de Montalk takes us clearly and concisely through her maze with its despairing blank turnings […] She’s a sophisticated, attentive narrator. Her renderings of pain are direct and unyielding […] [Her] pain still “insistently defines” her. Yet she recognizes that as a writer “suited to loneliness”, it’s something she explores as well as endures.’

‘'[E]ntirely engrossing and beautifully written [... she] ]turns the biographical eye in on herself and her poetic voice shines through in the prose [...] through her earliest days of medical recollection, to her nursing training, and most significantly, the ongoing saga of her experience with pain [...] I found a voice I recognised, and one that many others will also be able to relate to. For some it will be reassuring, in a way, to see experiences not dissimilar from their own on paper. For others it will be an eye-opening read––describing sensations and circumstances hitherto unknown. [...] an important and beautiful book, both tragic and hopeful.'

‘[A] beautifully rendered account that focuses keenly on an almost unbearable level of suffering caused by nerve pain. [...] when you read of poet and biographer Stephanie de Montalk's odyssey of suffering, in her superbly written account, you can only admire the fact that she still lives and writes. [A book that] deserves to be regarded as a classic on the singularly uncomfortable subject of ongoing human bodily suffering.'

Unity Books observed: 'It is a necessary, profound and instructive book for which there has not been a precedent - by that we mean there is nothing else like it and for which there has been a yearning gap. Like the writer Atul Gawande, de Montalk looks at science and medicine and human suffering and contemplates humankind. She does this through the lens of literature and through her own harrowing experiences. She writes paradoxically about a state that is "beyond words". In a year where there are no national book awards we could not let this book go unrecognised.'

How Does It Hurt?, is a study and a memoir of chronic pain - a condition which, despite advances in the science of pain and alleviation of acute or temporary pain, remains little understood and poorly communicated, while silently reaching epidemic proportions.

The narrative brings visibility and a measure of clarity to the lived experience of continuing physical pain. In particular, it confronts the paradox of writing about personal pain,

notwithstanding pain's resistance to verbal expression, and reflects on the ways in which other writers have lived with and written about pain; those writers include Polish poet and intellectual, Aleksander Wat,

English novelist and social theorist, Harriet Martineau, and French novelist, Alphonse Daudet, who believed that for victims of incurable pain, literature is 'a solace and relief [...] a mirror and a guide'.

In September 2018, How Does It Hurt, updated, will be published by Routledge in the UK and the USA as Communicating Pain: An exploration of suffering through language, literature and creative writing.

Below are a collection of interviews and audio reviews

1. Hurts like hell interview

2. Review with Mary McCallum

3. Narating pain review

"The pine tree leaning over the Kumutoto Stream rocked. Its crown, the highest in a stand of three, moved from west to east, brushing the clouds, gathering light from behind. Its foliage, high and low, rippled equally. I watched it sway through binoculars from my bedroom window. Framed the stumps on the mid-section of its trunk. Searched unsuccessfully for nests. Elongated the waving branches until there was stillness between them, and the city hill on which the pine stood became a mountain. Taoist Masters believed in the efficacy of trees, in their ability to absorb energy out of the earth and universal force from the sky. The more strongly rooted the plant, they claimed, the higher it extended to heaven. Plum trees were said to calm the mind, maples to disperse ill winds and lessen pain, and the tallest trees, notably pines, to be best for healing, especially when growing near running water.' (From Chapter 3, 'At the End of the Mind, the Body'.)"

'I was subjected to such a boycott as is unheard of in the annals of world literature. The whole thing [Potocki's obscenity trial and imprisonment] had a most unfortunate effect on my life. It extinguished my career as a poet.'

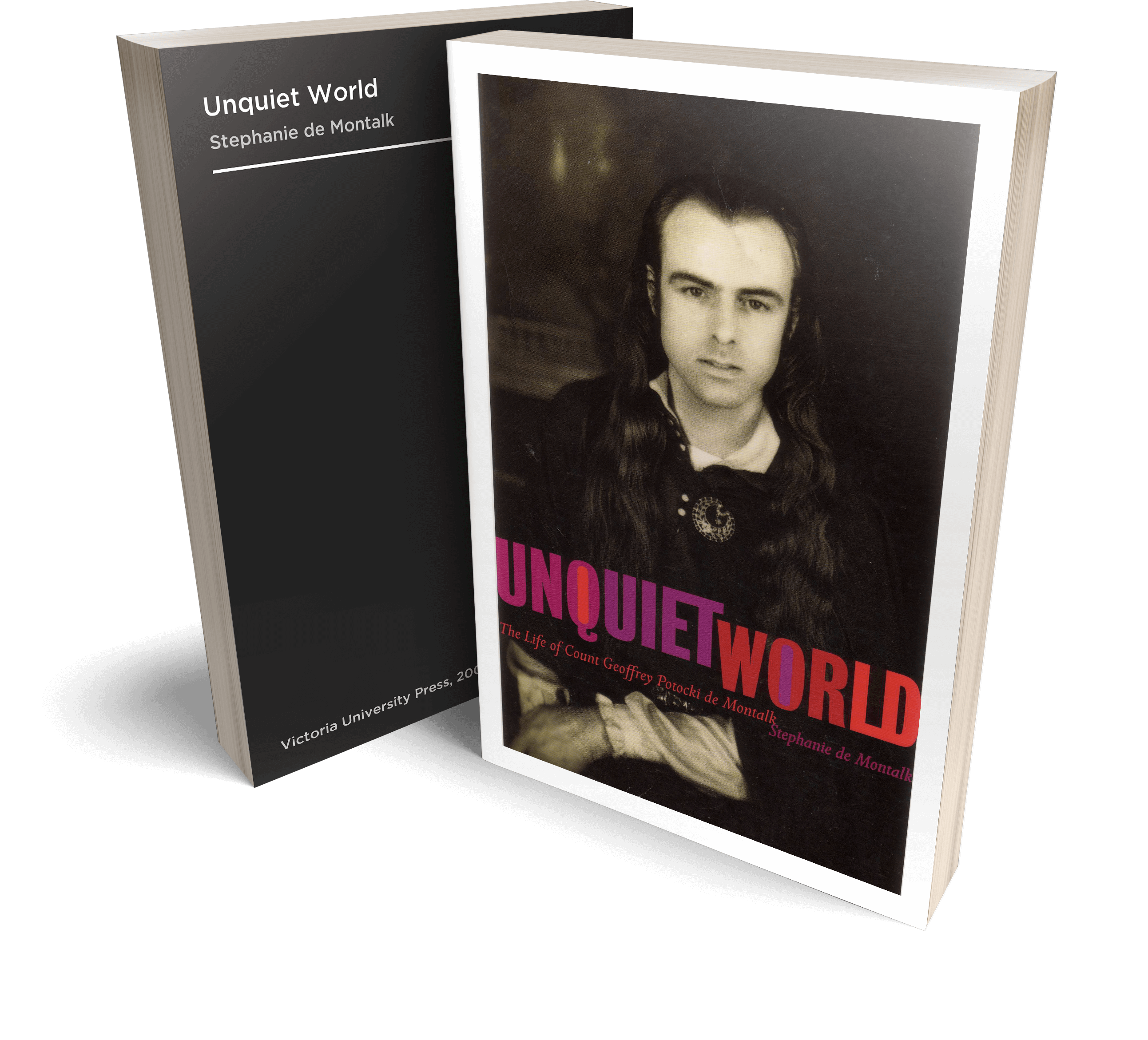

Poet, private printer, pamphleteer, pagan and pretender to the throne of Poland, Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk (1903-1997) - born in Auckland, New Zealand, and domiciled first in England

and then in France - was one of the great eccentrics of the twentieth century.

Unquiet World tells, for the first time, the full story of this fascinating and fugitive figure. It examines his difficult childhood; his role as a robe-wearing poet and polemicist; his way with women; his

splendidly vituperative communications with his 'enemies'; and his extraordinary obscenity trial in London, in 1932, for publishing (simply typesetting) a couple of translations by Rabelais and Verlaine,

and a bawdy poem of his own intended for his circle of friends.

The trial - during which he was supported by many of the leading writers of the day, including Leonard and Virginia Woolf - opened with Potocki in a cloak swearing by Apollo and intoning a pagan oath; the

outcome was six months in Wormwood Scrubs prison: a sentence described by W.B. Yeats as 'criminally brutal'. Rex v G.W.V.P. de Montalk - still cited in textbooks on criminal law - illustrated the extreme

lengths to which obscenity law could be stretched, and established, for the future, the defence of public good.

More than a biography, Unquiet World also provides insights into the literature of obscenity, the complexities of censorship, fringe right-wing politics and private press publishing.

Above all, it is a personal memoir of a poet cousin who left New Zealand to follow 'the golden road to Samarkand', but never completed the journey.

'The task of the poet is not to describe what actually happened, but the kind of thing that might happen according to probability or necessity [...] For this reason poetry is something more philosophical and more worthy of serious attention than history.'

This factually-based novel/poetic narrative imagines the events behind The Fountain at Bakhchisaray - Alexander Pushkin's 600-line poema of the impossible love of a Tatar khan

for a Polish countess held captive in his Crimean harem. The story is concludes with my own free translation of Pushkin's verse tale.

The year is 1752. Young Polish countess, Maria Potocka - abducted from her father's estate by Tatars during a slave raid into eastern Poland and carried in a cage to Bakhchisaray on the Crimean Peninsula,

languishes in the harem of the palace of the Tatar khans. She keeps a verse journal and works at a tapestry. She will soon die.

The year is also 1821. Alexander Pushkin - banished to Bessarabia, Southern Russia, for writing inflammatory political poems - is restless and depressed: a victim of government censorship, and also of his secret,

unrequited St Petersburg love for Sofia Potocka (from the same wider family as Maria). An unexpected meeting with Sofia in Odessa causes him to recall his recent visit to the Khan's palace, where he saw a

fountain of tears - a monument to a khan's unrequited love for a concubine, said to be Maria Potocka.

The interrelated stories of the captive countess and the exiled poet take place in alternating chapters, on a single day in Bakhchisaray, and between midnight and dawn in Odessa, respectively. They explore links

between distance, imagination and memory against a background of exile, death and the events that conspire in the making of a poem.

e : steph.demontalk@gmail.com

m : PO Box 6314 Wellington New Zealand