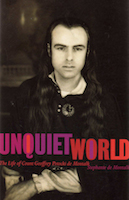

Cover Design

Sarah Maxey

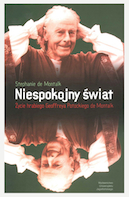

Cover Design

Witkowski (Paris)

Biography/memoir VUP, 2001

Polish translation, Jagiellonian University Press, Krakow, 2003, translator Maria M. Piechaczek.

‘I was subjected to such a boycott as is unheard of in the annals of world literature. The whole thing [Potocki’s obscenity trial and imprisonment] had a most unfortunate effect on my life. It extinguished my career as a poet.’

Poet, private printer, pamphleteer, pagan and pretender to the throne of Poland, Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk (1903-1997) — born in Auckland, New Zealand, and domiciled first in England and then in France — was one of the great eccentrics of the twentieth century.

Unquiet World tells, for the first time, the full story of this fascinating and fugitive figure. It examines his difficult childhood; his role as a robe-wearing poet and polemicist; his way with women; his splendidly vituperative communications with his ‘enemies’; and his extraordinary obscenity trial in London, in 1932, for publishing (simply typesetting) a couple of translations by Rabelais and Verlaine, and a bawdy poem of his own intended for his circle of friends.

The trial – during which he was supported by many of the leading writers of the day, including Leonard and Virginia Woolf – opened with Potocki in a cloak swearing by Apollo and intoning a pagan oath; the outcome was six months in Wormwood Scrubs prison: a sentence described by W.B. Yeats as ‘criminally brutal’. Rex v G.W.V.P. de Montalk – still cited in textbooks on criminal law – illustrated the extreme lengths to which obscenity law could be stretched, and established, for the future, the defence of public good.

More than a biography, Unquiet World also provides insights into the literature of obscenity, the complexities of censorship, fringe right-wing politics and private press publishing.

Above all, it is a personal memoir of a poet cousin who left New Zealand to follow ‘the golden road to Samarkand’, but never completed the journey.

Soon, warm with wine and rich food, he began to speak of his past. And he spoke as he had written, in twists and turns, darting from subject to subject with passion and wit and frequently with bitterness, but with little sense of exchange. He spoke of events, people and times in his life of which we had little or no knowledge, without explanation, without context. He spoke almost ceaselessly, pausing only to eat, drink and exchange smiles with his female host. John and I sat entranced. From time to time we glanced at each other and shrugged discreetly. Did he know we were there? When dessert finally arrived we were heavy with stories of self-proclaimed genius, political and legal intrigue, personal persecution and glorious ancestry. He had given a superlative performance. Much later we were to hear the stories again, and again, frequently word for word, with the same tilt of the head, the rage and softening of the blue eyes, the preoccupation with plot and counterplot and his own unrecognized genius. The devastating smile.

Soon, warm with wine and rich food, he began to speak of his past. And he spoke as he had written, in twists and turns, darting from subject to subject with passion and wit and frequently with bitterness, but with little sense of exchange. He spoke of events, people and times in his life of which we had little or no knowledge, without explanation, without context. He spoke almost ceaselessly, pausing only to eat, drink and exchange smiles with his female host. John and I sat entranced. From time to time we glanced at each other and shrugged discreetly. Did he know we were there? When dessert finally arrived we were heavy with stories of self-proclaimed genius, political and legal intrigue, personal persecution and glorious ancestry. He had given a superlative performance. Much later we were to hear the stories again, and again, frequently word for word, with the same tilt of the head, the rage and softening of the blue eyes, the preoccupation with plot and counterplot and his own unrecognized genius. The devastating smile.

Last time I was in London, I went to see the Old Bailey, or the Central Criminal Court as it’s more correctly described, wondering if a sense of the past was still there: the infamy of Recorder Judge Jeffreys, the remnants of trials, a sense of Newgate Prison on the site of which it was built and alongside which it later stood, its Justice Hall open to the air so that prisoners would not pass on typhus or gaol fever.

It was a grey city day and a cool wind blew about its facings of Portland stone and its tower, dome and bronzed figure of Justice, head in the sky. As it was summer I hoped I might see the laying of posies on the floors of the judges’ benches and ledges of the docks––a tradition between May and September from times when the flowers were used to lessen the smell and ward off disease from Newgate Prison next door. Disappointingly, I found little to suggest the ambience of the 1930s. Posies were now carried into court only once a year, and the small session-house in which Potocki had been tried had been extended. Moreover, I was told by a clerk, the courtroom of the Recorder had been rebuilt, following its destruction by bombs during the Second World War.

I wasn’t seeking the weight of history, more a sense of place. This was the building Potocki had entered with confidence, having insisted on trial by jury, believing this would be his big moment. He had told me: ‘After all, I regarded myself as having been wrongfully arrested and contemplated a counter-attack’, a statement which suggested that, had he so wished, he could have dispensed with the jury and chosen the less spectacular route of a defended hearing before a judge. The statement also suggested that The Well of Loneliness, found to be obscene in 1928 by a magistrate, without recourse to literary expertise or writers waiting in court to give evidence, may have featured in his thinking. ‘Why hide away?’ he might have asked himself. ‘As a former student of the law, I know my crime has been minor and the worst I can expect is a fine. Why, then, pass up the chance to showcase literature, wrongful arrest, freedom of expression? Myself, as a poet?’

On the morning of the trial, having prayed to his gods, and joined Minnie, his mistress and [New Zealand friend Douglas] Glass, who was also staying at Edith Road, in a breakfast of eggs, bacon, toast and several cups of hot sugared tea, Potock had dressed––for effect. While a more cautious defendant might have favoured a sober appearance, he had combed out what the News of the World would describe as his ‘wealth of luxuriant long hair’ and settled for his cloak and open-toed sandals: word had gone out and a large crowd was expected in the public gallery––literary figures, censorship experts, reporters and female admirers.

On the morning of the trial, having prayed to his gods, and joined Minnie, his mistress and [New Zealand friend Douglas] Glass, who was also staying at Edith Road, in a breakfast of eggs, bacon, toast and several cups of hot sugared tea, Potock had dressed––for effect. While a more cautious defendant might have favoured a sober appearance, he had combed out what the News of the World would describe as his ‘wealth of luxuriant long hair’ and settled for his cloak and open-toed sandals: word had gone out and a large crowd was expected in the public gallery––literary figures, censorship experts, reporters and female admirers.

With time in hand and a sharp wind from the north-east scattering snow in the suburbs, he and his friends made their way to the Old Bailey, where they passed beneath the solemnity and occasion of the words of the Recording Angel––Defend the children of the poor and punish the wrongdoer––without any particular concern, and ascended to the central hall, two marble steps at a time. Then, after meeting with du Cann, and encouraged by Glass, who would remain in the hall to direct supporters, Potocki kissed Minnie, surrendered to his bail and was taken into custody with a flourish, for the duration of the trial.

He followed a warder to a cell beneath the courtroom, gathered the sweep of his cloak around him for warmth, paced for a moment and then took a seat on a bench. The cell was bare, with toilet arrangements visible from the door, but this did not bother him. Potocki, the prisoner, was simply passing through. Tonight he and his friends and their girlfriends would dine out, order wine, toast his performance. Tomorrow there would be the dailies. At the end of the week, editorials. Beyond that, flattering impressions of fame. He took his fountain pen and some loose sheets of paper from his pocket, and turned his attention to the speech he had started the previous evening.

At this point it occurred to me that the issue of truth was becoming a preoccupation. It kept rounding the corner, asking: ‘How is it that you think you knew Potocki? You were a late-comer to his life, an occasional participant. Where are you finding this truth? In the transcripts of interviews? Dialogue? In letters (the true “fossils of feeling” that Janet Malcolm speaks about in her meditation on biography)?’

One day, my mind went back to the small room in the city where I had unpacked the archive. Here, quite early on, as I was kneeling on the floor––back stiff, knees sore––from beneath the dust, and pages still damp with the earth and rain of France, a sense of Potocki I had not previously recognized had begun to emerge. Here in the quiet room with his letters, the small notes to himself, the invoices, lists and receipts, the ‘fact’ of him had become overlaid with his familiarity––the scent and fine ash of incense he left in circles on his desk; his hands and feet, lean, always tanned; the small movements at the side of his mouth when he was concentrating or reading. I recalled his quiet way with paper, his light step, and each morning as he left the house and I checked his room, the undented stillness of his bed.

One day, my mind went back to the small room in the city where I had unpacked the archive. Here, quite early on, as I was kneeling on the floor––back stiff, knees sore––from beneath the dust, and pages still damp with the earth and rain of France, a sense of Potocki I had not previously recognized had begun to emerge. Here in the quiet room with his letters, the small notes to himself, the invoices, lists and receipts, the ‘fact’ of him had become overlaid with his familiarity––the scent and fine ash of incense he left in circles on his desk; his hands and feet, lean, always tanned; the small movements at the side of his mouth when he was concentrating or reading. I recalled his quiet way with paper, his light step, and each morning as he left the house and I checked his room, the undented stillness of his bed.

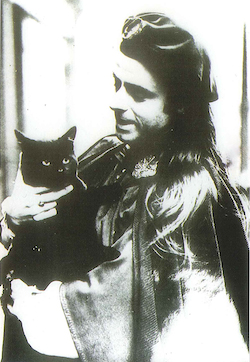

Had the process of biography and memoir begun with my first awareness of him? With my mother’s impatient remark [‘You’re just like the Count!’], or the photo with the cat he called Franco––the first time I noticed him?

The documentary screened on The Tuesday Documentary, TV1, in 1987.

Writer/Producer: Stephanie Miller (de Montalk)

Director: Ian Paul

A top ten, ‘Best of 2001’ book, The Dominion, 29 December 2001.

A ‘top four’ book of 2001, David Hill, ‘Nine to Noon’, National Radio, December 2001.

A ‘Favourite’ book of 2002, The Sunday Star Times, 29 December 2002.

‘Every once in a rare while, a subject and an author admirably suited to each other connect and the result is a book of outstanding interest and merit. Unquiet World is one such volume. [...] [L]ike most poets [de Montalk] writes prose very well. This quality is yet another that lifts this book from the domain of biography into that of literature. What she has to say about de Montalk senior is clever, vivid and clear. She presents the crumbling Provencal villa in which he lived his last years as a metaphor for his entire life. And her asides are devastatingly apt. [...] The book does what every good biography should do. [...] It has to be a favourite for the newly introduced category of biography in next year’s Montana Awards.’

Michael King, ‘Pretender to the Throne’, The Dominion, 17 November 2001.

‘Stephanie de Montalk succeeds in bringing her implausible relative to plausible life. His various exploits on a world stage are set in a meticulously researched analysis of the context of its times, and in openly acknowledging a complex and shifting personal relationship with her quarry, she charts the subjectivity that must go into the making of any biography.’

Ruth Brown, The Times Literary Supplement, 27 December 2002.

‘ ... a magnificent humane book [...] which also happens to be one of the best books of 2002 (even though it came out at the end of 2001).’

Gregory O’Brien.

‘ ... a judicious, stylish and entertaining book. De Montalk (the author: she calls her subject, as he would have wished, Potocki) wisely decided against the kind of biography, with every day accounted for and every fact footnoted, that is a reward, or punishment, for tangible achievement. [...] She puts herself in the picture, pursuing her cousin: a quest for Potocki. He was in many respects a classic eccentric. De Montalk has read the literature on eccentricity, but she has not been content to dismiss him with a label. She has sought the springs

of the man behind it. She has been thorough. From time to time I quibbled and asked questions – ‘Is she too indulgent of his outrageous bigotry? What does she really think of his poetry?' – then found her grappling with the same questions

Dennis McEldowney, ‘Mandatory Count’, New Zealand Listener, 1 December 2001.

‘[de Montalk’s] narrative of NZ literature’s most spectacular expatriate is one of the most consummate and compelling stories I’ve read ... well, this millennium. [...] [She] lucidly outlines the passions that endured through the posturings: fidelity to free speech, Polish integrity, the immanence and permanence of beauty. [...] She’s quite a presence in the narrative.’

David Hill, ‘Passions and Poses’, Weekend Herald, 8—9 December 2001.

‘The book is a witness to deliberations and search for a method of unraveling a difficult personality. It seems the author, writing about Potocki, sketches her own portrait, which to me appears more alluring than her subject. [...] What then are Potocki’s achievements? The book indicates that they are the reprints, translations and verses. But the greatest achievement [...] is Stephanie de Montalk, who undertook the task of finding some sense to his life. The result is a quality product.’

Maja E. Cybulska, ‘In My View: The Pretender and the Author’, Tydzien Polski (The Polish Weekly), London 14, December 2001.

Review translated by S. Manterys.

‘ ... a masterpiece of personal essay writing’.

Gregory O’Brien, ‘Marketplace or Laboratory’, New Zealand Listener, 30 August 2008.

‘[Her] explanation of the Count’s obscenity trial is masterful in the thoroughness and precision of her analysis. It should be used as a model of how extra-legal factors affect outcomes in every law school’s “Law in Society” course. [...] The book ends with the funeral of an unnamed stranger in France, coincidentally taking place near Geoffrey’s grave. The stranger's family will never know they close one of New Zealand’s best memoirs.’

Bill Hastings, ‘Something Nobody Counted On’, New Zealand Books, March 2002.

‘This fascinating book [...] is not a standard biography [...] Rather, the arrangement of the material largely reflects de Montalk’s search to understand a cousin whom she liked despite major differences in political and social values. (And I also imagine, despite Potocki’s considerable charm, his ability to be exasperatingly himself.)’

John Dickson, ‘Trying to Make Sense of an Eccentric’, Waikato Times, 27 October 2001.

‘Potocki’s extraordinary career is examined – with sympathy but definitely not without criticism.’

Iain Sharp, ‘Poetic Injustice’, Sunday Star Times, 30 September 2001.

‘What makes the journey in pursuit of [Potocki] is the calm, honest guide that cousin Stephanie proves to be. [...] Stephanie’s book, based on personal interviews, observation and careful study of a mountain of mouldy papers, is a fascinating peeling back of Potocki’s personality.’

Martin Doyle, ‘Poetry and Bonking – Call Me Count Geoffrey’, Capital Times, 17 October 2001.

‘Stephanie de Montalk’s engaging memoir/biography [...] gives a provocative perspective on one of New Zealand’s more enduring eccentrics. [...] [She] has done a service by restoring [Potocki] to a richer view, and providing a necessary lens on eccentrics in general.'

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman, The Press, Christchurch, 15 December 2001.

‘[De Montalk] does not attempt to write a traditional scholarly “objective” biography, but rather she tells both [Potocki's] story and, at the same time, the story of her and her family’s relationship with him in his later years, and of her own attempts to understand him and write this book. The result is a sympathetic portrait of a man who might have been treated as a figure of fun, and at the same time an honest account of her attempt to come to terms with his extreme self-centeredness and eccentricity and to see their probable origins in his painful upbringing by an authoritarian stepmother and several aunts. The book is a sensitive exercise of sympathetic imagination.’

Lawrence Jones, ‘The Kiwi Who Laid Claim to the Throne of Poland’, Otago Daily Times, 15 December 2001.

‘Stephanie de Montalk does better justice to her second cousin than any mere review. This critical biography of a difficult, colourful aristocrat makes us yearn for the eccentric.’

Emmet McElhatton, ‘Biography Stirs the Inner Eccentric’, Northern Advocate, 21 December 2001.

‘ ... The magnetism is sensitively captured by his cousin’.

Catharina van Bohemen, ‘Affectionate Portrayal of an Eccentric Relative’, Evening Post, 2 November 2001.

‘ ... a compelling read – I for one couldn’t put it down once I started. [...] My recommendation? READ IT!’

Gillian Cameron, ‘Report’, New Zealand Poetry Society Newsletter, November 2001.

‘ ... an entertaining and compelling read. [...] the chronological development of Potocki’s life and de Montalk’s relationship with him [...] unfold side by side. In this way the reader is able to at once make sense of his life but also be baffled and intrigued with him just as the author was.’

Rose Swindells, Salient #13, 2001.

‘ ... it is from [de Montalk’s] relationship that much of the work’s pleasure derives. While never descending into naïve idolatry [she] has obviously approached the study of her hirsute relative with the vigor and fascination of a fellow writer. [...] a sound attempt to preserve the work and record the life of this most extraordinary man’.

Michael Redmond, London Magazine, July 2002.

‘[Unquiet World] has the authentic Potockian tone to it. I can almost hear the Count’s voice as [de Montalk] re-tells some of his anecdotes, and her text has revived many half-forgotten memories. The entertaining style skillfully conceals the thorough research she has undertaken while writing it, but she manages to account for his early life in New Zealand, and his European adventures, in a way which makes better sense of an extraordinary life than I would have thought possible.’

Roderick Cave, The Private Library, 2002.

‘ ... the most extensive source I know [of the ‘many accounts’ of Potocki’s life] and the most fascinating’

Rigby Graham, ‘Count Potocki of Montalk’, Parenthesis 12, November 2006.

‘Wellington poet Stephanie de Montalk writes as the fascinated, caring cousin of this self-mythologiser and manages to flesh out his elusive character and make sense of his baroque literary endeavours.’

North and South, December 2001.