Cover Design

Sarah Maxey

Victoria University Press, 2006

‘The task of the poet is not to describe what actually happened, but the kind of thing that might happen according to probability or necessity [...] For this reason poetry is something more philosophical and more worthy of serious attention than history.’

From Poetics, IX, Aristotle

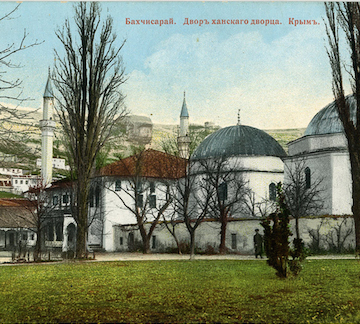

This factually-based novel/poetic narrative imagines the events behind The Fountain at Bakhchisaray – Alexander Pushkin’s 600-line poema of the impossible love of a Tatar khan for a Polish countess held captive in his Crimean harem. The story is concludes with my own free translation of Pushkin’s verse tale.

This factually-based novel/poetic narrative imagines the events behind The Fountain at Bakhchisaray – Alexander Pushkin’s 600-line poema of the impossible love of a Tatar khan for a Polish countess held captive in his Crimean harem. The story is concludes with my own free translation of Pushkin’s verse tale.

The year is 1752. Young Polish countess, Maria Potocka – abducted from her father’s estate by Tatars during a slave raid into eastern Poland and carried in a cage to Bakhchisaray on the Crimean Peninsula, languishes in the harem of the palace of the Tatar khans. She keeps a verse journal and works at a tapestry. She will soon die.

The year is also 1821. Alexander Pushkin – banished to Bessarabia, Southern Russia, for writing inflammatory political poems – is restless and depressed: a victim of government censorship, and also of his secret, unrequited St Petersburg love for Sofia Potocka (from the same wider family as Maria). An unexpected meeting with Sofia in Odessa causes him to recall his recent visit to the khan’s palace, where he saw a fountain of tears – a monument to a khan’s unrequited love for a concubine, said to be Maria Potocka.

The year is also 1821. Alexander Pushkin – banished to Bessarabia, Southern Russia, for writing inflammatory political poems – is restless and depressed: a victim of government censorship, and also of his secret, unrequited St Petersburg love for Sofia Potocka (from the same wider family as Maria). An unexpected meeting with Sofia in Odessa causes him to recall his recent visit to the khan’s palace, where he saw a fountain of tears – a monument to a khan’s unrequited love for a concubine, said to be Maria Potocka.

The interrelated stories of the captive countess and the exiled poet take place in alternating chapters, on a single day in Bakhchisaray, and between midnight and dawn in Odessa, respectively. They explore links between distance, imagination and memory against a background of exile, death and the events that conspire in the making of a poem.

Bakhchisaray, during the afternoon rest:

‘Come!” Zarema beckons. ‘Halide is in the birthing room. Nirali asks for you. Quickly, before Alena can see.’

She darts forward and pulls Maria’s arm, dislodging her needle and embroidery frame.

Maria knows she is dreaming but does not want to stop

She has never been to the room beyond the curtained door at the end of the hall. She has watched Nirali and the wet nurse arrive with their burdens; the servants rush by with towels and ewers of hot water, and the dry nurse with shawls and small garments. She has crept to the curtain and listened with the vigilant eunuch to straining cries worse than the distress of foaling mares and the imagined sufferings of wounded men; waited for Nirali’s call, ‘Allah akbar, God is great,’ and the demented chorus of servants and wives flicking their tongue tips on the roofs of their mouths, until she could listen no longer

The next day, in compliance, with a long-stemmed rose at the door, she has visited the awakening room; admired the baby held up and dandled; seen the mother, mysterious and drained like the body of Christ beneath her downy coverlet, a red ribbon around the neck of her water jug if the child is a boy, the handle, if a girl.

Zarema, confiding the perils of childbirth, has described women with shivering fits and after-pains. Shiny, swollen white legs. Breast of iron wrapped in hot cloths. The melancholy of gentle Nurham, who forsook her child and spent a year in the windowless room.

In the dream, there is no keeper at the door, no sound on the other side of the curtain, little light

Zarema drags Maria through a vestibule into a candled passage

Around the corner there is a second door and, briefly, the muffled cry of an infant.

Nirali reveals herself, kneeling before a woman hobbled to a carved hardwood chair by her wrists and ankles in the birthing position.

Halide?’

Nirali presses the woman’s belly. ‘The baby was born safely,’ she says, ‘but the long clot does not come. We should lift her to the bed.’

This is not Halide beneath the turgid glare of the lamp, in a soiled nightgown, with a bit between her teeth, trying to throw herself to the floor. The scarfed head is small, the face oval, and the eyes, although familiar, are blue.

Zarema says, ‘She cast away the world and drank from a bitter spring. It is best that she die.’ The woman wails and tosses her head.

‘In this room,’ Zarema continues, ‘her high birth and life of ease count for nothing; her religion and sloping white shoulders do not matter; her education was unnecessary. Here she has borne a daughter who will be ignorant of history and learn only to sew and share her master’s affection. The girl will, in turn, give birth to five children. She will waddle and suffocate in spite and bad air. Carry stranglement within her from darkness to sunrise to sunset, like a leech left on the skin until it is satisfied, lest it relinquish a tooth to the wound.’

They speak Turkic: herself, Nirali and Zarema, and the woman who is not Halide. And Persian. Perhaps they also speak Arabic and English. In the urgent room, in its inscrutable depth, the tongue’s rapid interpretation of thought is important, not its exactness of language.

Odessa, 3.30am

Alexander Sergeevich had been relaxed on the brig: He thinks back to the passage to Gurzuf in the creak of timber as the ship, undergoing refitting and free of its cannons, rode high in the water. He recalls the enjoyment of bread, salad and fresh lobster in the captain's cabin, and, after the evening meal, sitting astride a crate of fuses and shells on the deck with a bottle of white wine while the Raevskys settled between rifles and keys of gunpowder in their hammocks.

He summons a night of true darkness. The captain had sent a man aloft with three lighted bell jars covered with canvas, and sailed on, taking advantage of the breeze. The lamps glowed high on the mast, making little impression below. The moon caught itself in the sails, leaving the ropes, ladders and cluttered deck as abstruse as the horizon.

[...]

At this moment, tonight, in Odessa’s same southern air [...] Alexander is of the view that exile, unwilling and resisted, implies a situation of commendable separation; affirms precaution and penance, certainly, but also remission – or at least intervals where entrancement is possible. [...]

He reminds himself that, in involuntary exile, he had toured with the tolerant and cultured Raevskys in the heat, contemplation, implicit freedom and latitude of the East; known kif, or nothingness, and the commerce of passivity and strange southern magic that had lightened his exile and relieved the burden of Sofia and his unfulfilled love.

In the Caucasus and Crimea he had lain in exclusion’s fine wicker chair. Sipped from the neck of its oriental flowers, at once vivid and pale, curious and beautiful, not thinking beyond Bakhchisaray where he would end his journey and travel to General Inzov at Kishinev.

He had also conceded that the Eastern effect was one of illusion. That behind the mosques and bazaars, on the other side of the narrow baked roads, the fountains and languid climate of the female submission in the thirty-six pipe-smoking states of the sultans, there was likely to be the same bad food, mayhem and slavery, the same use of pistol and sword that there had always been, and the apparent tolerance was a splendid array visible only to emigres who, like Byron, Bronevsky and himself, watched from a window, always at a distance.

He admits that, in Crimea, the spectre of Ovid’s involuntary exile had yet to haunt him. He had not then travelled to the backward streets and squares of the Danubian settlements close to the shore on which the Roman poet had laid the ostracized gods of his fathers and left his ashes; to the forlorn coast to which Ovid’s own poetic irreverence and view that life is neither moral or elevated had taken him.

He had yet to plan his visit to Akkerman, and the piece of ground appointed Ovid’s grave where, moved by the poet’s separation from lovers, library and friends, he will doubtless weep for him, read his work from the French translation he has borrowed, and ask himself if he is destined to follow the same fate, with the tsar his Augustus, Bessarabia his Tomis, and the Black Sea his coast at the edge of the Empire.

The Fountain of Bakchisarai is a Russian ballet inspired by the 1823 poem by Alexander Pushkin of the same title. With music by Boris Asafyev and choreography by Rostislav Zakaharov, the ballet premiered in St Petersburg (then Leningrad) in 1934 at the Kirov Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet (now the Mariinsky Theatre).

‘A jewelled box of mirrors [...] This may be the most exotic story yet written in this country. [...] Stephanie de Montalk is at once our Scheherazade and Pushkin, Ovid and his Nightingale Philomela, singing a rare and complex melody [...] Imagination is not just the engine that drives the writing: in this novel it is almost a force of of the nature. [...] New Zealand writing is the richer and lovelier for it.‘

Chris Price, author of Brief Lives, speech, 10 October 2006.

‘A high quality work of intellectual fiction [...] a powerful and compelling re-creation of two parallel situations and personages [...] a valuable work [...] rich in biographical, psychological, and mythological contexts, precise in many details concerning both Pushkin’s childhood and youth and the complex phenomena of Eastern European history and culture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and profound in its exploration of the themes of creativity, of responses to surrounding reality, and of the (re)creation of one’s personality in letters, dreams, life and art.’

Svetlana Klimova, Linguistic University of Nizhnii Novgorod, for the Pushkin Review 15 (2012): 165-67

‘... dense with imagery and suggestion [...] When I had finished reading it, I turned back and read it again. It’s a book that rewards close attention, and – like Maria [who keeps the khan at a distance] one that refuses to give up its treasures easily. [...] It offers much to admire, to listen to with the inner ear, to savour, to ponder and to puzzle about. My recommendation is to [read this book] at least twice. I’m not joking – it really does reward that effort.’

Nelson Wattie, ‘The Poet and the Concubine’, The Dominion Post, 13 January 2007.

‘The language is consistently rich, often purely beautiful. Montalk is a poet:

“The moon flings dust in Maria’s face: the dust of bakeries, vegetable sellers and barbers; the white dust of the poplars behind the Great Mosque.”

Abby Cunnane, Capital Times, 15 November 2006.

‘Fantastically ambitious [...] a sort of imaginative recreation of an imaginative recreation [...] I think it’s wonderful [...] a remarkable book [...] She has Pushkin imagine at a certain point, “as long as the chronicled air is breathable historical approximation is sufficient”. And this chronicled air is definitely breathable.’

Harry Ricketts, ‘Speaking Volumes’, Nine to Noon, Radio New Zealand, December 2006.

‘Invariably and stylishly lifted by sweeping movements of plot and language. [...] The plotting of The Fountain of Tears is one of its great pleasures.’

Elizabeth Smither, ‘The Khan’s Wife’, New Zealand Listener, 18-24 November 2006.

‘... a singular achievement [...] De Montalk removes Pushkin from the literary canon for a day so that we may get to know him as a living man, before his works have gained their place on the world’s bookshelves. [...] One feels a greater affinity with Pushkin after reading

this book and seeing him wrestle with captivity and memory in the early hours of an Odessa morning. [...] Ultimately the two stories, and their two vanished characters, intersect through a physical medium, the fountain of tears title. [...] the worlds of Maria and Pushkin are successfully evoked [as are the story’s] meditative explorations of the ideas of captivity, memory and the fluidity of time. [...] a further development from an original and innovative New Zealand writer.

Robert Metcalf, The Lumiere Reader, 5 January 2007.

‘I am surprised that Stephanie de Montalk is the first (as far as I know) to put this rich, romantic material to good use, in the form of a novel generously interspersed with verse. De Montalk’s experience as a poet and biographer makes her the ideal author for such a pursuit.

Amy Brown, Salient, Issue 25, October 12, 2006.